New publication: a chance discovery of an extraordinary dragonfly migration

A visit to Bonaire

In October last year (2019), as I was skimming through reports of sightings of migratory dragonflies on the platform iNaturalist. I stumbled upon something extremely surprising. Clicking in the settings on iNaturalist to show observations of “vagrant emperors” on the world map, I saw a red dot gleaming in the Caribbean. Of course, I thought it had to be some sort of mistake. The vagrant emperor, though an extraordinary migrant, observed on faraway islands such as the Maldives and Iceland, has a core distribution in tropical Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean. Not the Americas.

But it was true. Vagrant emperors have been seen in the Caribbean!

I wrote about this fascinating example of long-range range expansion on the blog on the 25th of November: Emperor of the Seas

And as I was on my way to the Caribbean that year, in late November to mid December, to study Caribbean reef squids, I scanned the reports and check-lists for the island I was visiting: Bonaire. But no one had seen any vagrant emperors there. However, both of the neighbouring islands, Aruba och Curaçao, had numerous reports of this paleo-tropic (“old world”) migrant.

So, I thought to myself, it would be extremely cool if I was to see a vagrant emperor on Bonaire, then I would be the first to report on it.

The main road through Washington-Slagbaai National Park, Bonaire. Photo: Eva Ehrsten

The chance discovery

The main purpose of the visit to Bonaire was of course to study squids, ie we would spend most of our time under or in water, diving and snorkelling.

But, we did go to the national park on the north of the island: Washington-Slagbaai.

And, as we are driving down the main road of the park, surrounded by immense, prickly cacti, dry scrub and with the occasional gimps of pearly-eyed thrashers and caracaras, we see a flash of a big dragonfly.

It swoops by, and we get out of the car to try to see it better. We are barely able to catch it on camera.

But we do get two photos. The clear blue saddle on the abdomen is unmistakable.

It is a vagrant emperor!!

A vagrant emperor on Boniare, Photo: Alex Hayward

Previous observations

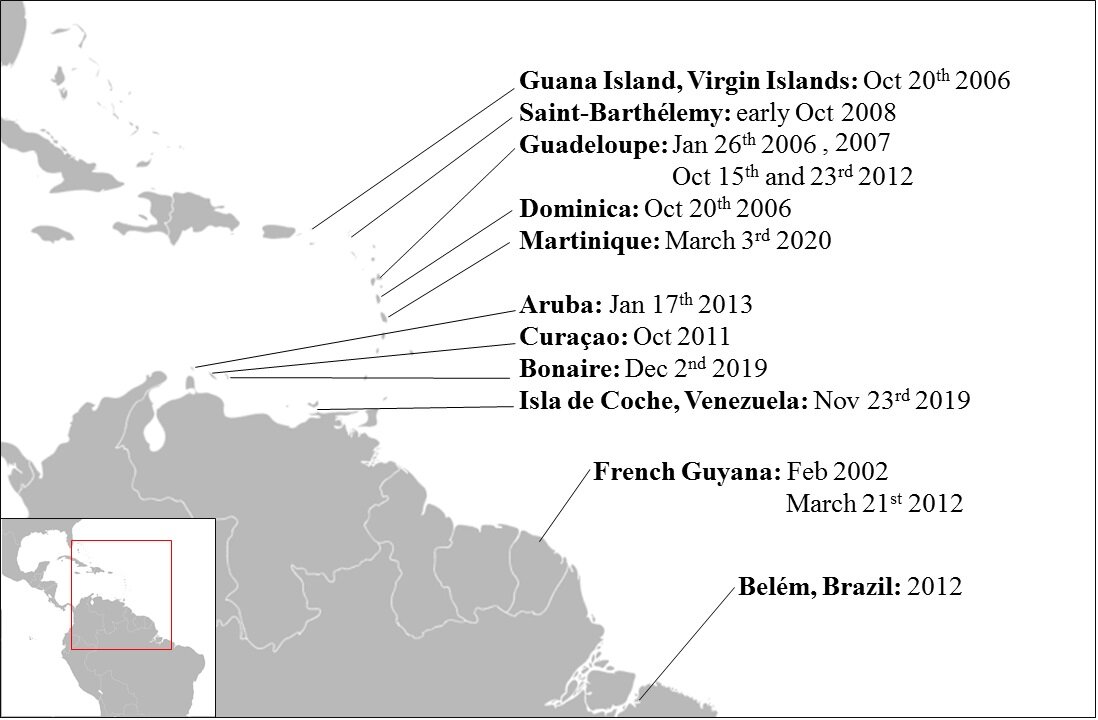

Upon my return from Bonaire, I exhaustively search the literature for all Neotropical reports of vagrant emperors, and created a map showing all observations I could confirm.

With the first ever observation in French Guyana in 2002, the species has since been seen in Guadeloupe, British Virgin Islands, Curaçao, Aruba, Brazil, Venezuela, Saint-Barthélemy, Dominica and Martinique (map below).

Places and dates for observations of vagrant emperors in the Neotropics (Hedlund et al 2020)

Where and how?

Vagrant emperors may be obligant migrants, travelling with the rain-bearing winds of the InterTropical Convergence Zone (ITZC) across Africa and Asia, but they do not regularly fly over the Atlantic Ocean. So how did they end up in the Neotropics (“new world”)?

Just as explained in a previous blog post (here), there are high-altitude trade-winds that travel from tropical Africa across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and South America. These winds do occur roughly at the same time and place as large-scale migrations of vagrant emperors in Africa.

Thus it is hypothesized that a trade wind event carried vagrant emperors from West Africa to the Neotropics. As the species appears to be firmly settled in the region, being observed on more and more islands and sites, the trade wind event could have happened several times, or included several individuals.

Modelled trajectories of the displacement of desert locusts arriving in the Caribbean in 1988 (Rosenberg and Burt 1999)

The locust case

On several occasions in 1988 desert locusts, the “plague” grasshoppers of Africa that swarm in millions during their migration, were blown across the Atlantic from Africa.

However, unlike the vagrant emperor, none of the locusts established and survived in their new home. Interestingly though, genetic studies on the ancestry of swarming Neotropic grasshoppers have shown that they all originated in Africa, suggesting that chance displacements from Africa, assisted by seasonal winds, CAN give rise to a new population, even species.

Known from the Bible. Source: Iwoelbern. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The published article

It is still unclear what will become of the vagrant emperor in its new home. It may spread, and conquer the world, just like the globe skimmer dragonfly has. The two species are similar in their ecology, and reliance on the ITCZ.

If you want to read more about the vagrant emperor in the Neotropics, our findings were published today in an article online, for the journal International Journal of Odonatology:

New records of the Paleotropical migrant Hemianax ephippiger in the Caribbean and a review of its status in the Neotropics

The authors on our last night on Bonaire, doing the underwater sign for squid

We end our publication with the sentence:

“The arrival of a new insect apex predator such as the vagrant emperor may have considerable ecological potential and is the setting of a natural experiment in progress.”

References

De Marmels, J. (2007). How and when did the Vagrant Emperor, Hemianax ephippiger (Burmeister, 1839) arrive in the Caribbean? Argia , 19 (2), 16.

Hedlund, Ehrnsten, Hayward, Lehmann and Hayward (2020) New records of the Paleotropical migrant Hemianax ephippiger in the Caribbean and a review of its status in the Neotropics. International Journal of Odonatology. https://doi.org/10.1080/13887890.2020.1787237

Lorenz (2009). Migration and trans-Atlantic flight of locusts. Quaternary International , 196 (1–2), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2007.09.038

Lovejoy et al (2006). Ancient trans-Atlantic flight explains locust biogeography: Molecular phylogenetics of Schistocerca . Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences , 273(1588), 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3381

Machet and Duquef (2004). Un visiteur inattendu et de taille! … Hemianax ephippiger (Burmeister 1839) capturé à la Guyane française. Martinia , 20 (3), 121–124

Rosenberg and Burt (1999). Windborne displacements of Desert Locusts from Africa to the Caribbean and South America. Aerobiologia , 15 (3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007529617032