From Gambia to Grand Canaria

Photo by Elaine W.

Unlike the world’s human population, the year 2020 is no different to migratory animals, who not only have the freedom to move, but can enjoy clearer skies and less noise pollution from cars and planes this year.

Early in February, before most countries went on lockdown and travel ceased, reports started to come in about a massive swarm of insects in West Africa…

Vagrant emperor by the coastal dunes of the Gambia, Feb 16 2020, by Allen Holmes

Vagrant emperor, Tujering, The Gambia, Feb 18 2020, by Allen Holmes

It started with a few groups of individuals, flocking in The Gambia along the shores. But from a few individuals, the moving flocks grew, and grew, and grew, until an enormous swarm of vagrant emperors took over the West African coastline.

And then the swarm moved…

By the end of February, it had not only reach the coastal dunes of Senegal to the north, but all the way to the Canary Islands.

Vagrant emperors, Gran Canaria, Feb 26th 2020, by Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

Vagrant emperors, Gran Canaria, Feb 22nd 2020, by Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

In the Canaries however, it seemed like the swarm diminished, scattered. Observers in Spain anticipated it to arrive on their shores, and some individuals were seen. But no swarm.

2019 saw a great influx of vagrant emperors in Europe from the east, as noted by colleagues on Cyprus in April (read a blog post about it here). But migratory movements of vagrant emperors along the western regions of the Mediterranean, for example observed on the Canary Islands, Malta and Sicilian islands, are also fairly annual events.

Vagrant emperor, The Canary Islands, Lanzarote, 24th Feb 2020

Vagrant emperor, Gran Canaria, Feb 26 2020, by Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

Vagrant emperor, Gran Canaria, Feb 26 2020, by Pablo Martinez-Darve Sanz

The great migratory movements of the vagrant emperors emerging in Africa do not solely occur along coast, the dragonflies have also been observed in hundreds in central Sahara, and around ponds and pools in the mountains of Algeria.

This suggests that the “millions” seen in on the coasts of Senegal and The Gambia in February this year, are paralleled inland and all over the African continent. The numbers on the move may be astronomical.

Sites were large swarms of migrating vagrant emperors have been reported in spring 2020

Several species of dragonflies are often observed in these mass-emergence and mass-movements phenomenon. Together with the vagrant emperor, species like the red-veined darter (Sympetrum fonscolombii), the broad scarlet (Crocothemis erythraea), globe skimmer (Pantala flavsecens) and the keyhole glider (Tramea basilaris) are often seen on migration, sometimes in mixed-species swarms.

Vagrant emperor, Toubakouta, Saloum Delta, Senegal, March 1st 200,0 by Johan Van 't Bosch

The sudden mass appearance of migrant dragonflies is a consequence of their adaptation to utilise the monsoon rains in Africa. These rains transform arid lands and dried-out ponds from deserts to lush habitat, and mobile species are able to make use of this seasonality.

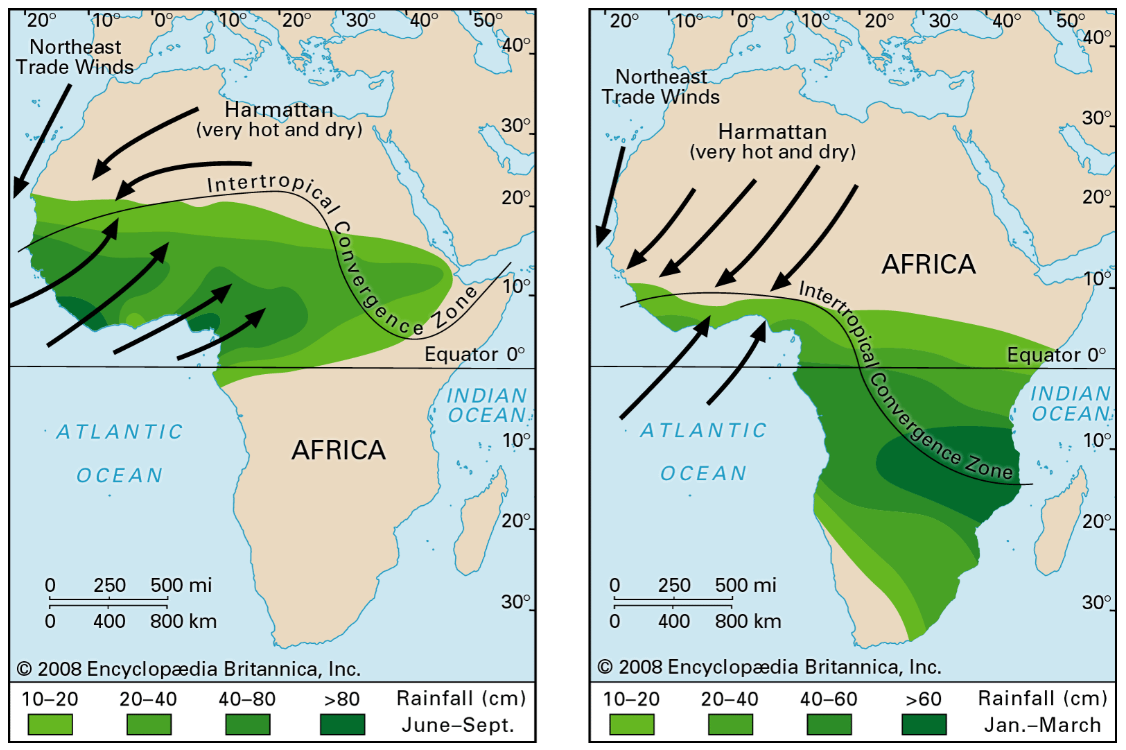

The individuals found on migration in winter and early spring are the offspring produced during wetter months in autumn in West Africa. As atmospheric pressure oscilliate over the African continent, moving the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone, not only rains come and go, winds change direction. As wet, cool air meets dry, hot air, The African Easterly Jet is formed. The AEJ blows from east towards west, along the ITCZ front, and carries air all the way across the Atlantic to the Americas.

This is the aerial motorway that sometimes brings swarms of locusts, and sometimes even vagrant emperors, from Africa to the Caribbean (read more about that here). It is also plausible that it was the AEJ that carried dragonflies from the Gambia and Senegal to the Canary Islands in February 2020.

The West African monsoon, creating heavy rainfall in West Africa in late summer and autumn. By: Encyclopaedica Britannica

References

Corso et al (2012)Annotated checklist of the dragonflies (Insecta Odonata) of the islands of the Sicilian Channel, including the first records of Sympetrum sinaiticum Dumont, 1977 and Pantala flavescens (Fabricius, 1798) for Italy. Biodiversity Journal, 2012, 3 (4): 459-478

Dumont (1977) On migrations of Hemianax ephippiger(Burmeister) and Tramea basilaris (P. de Beauvois) in West and North-West Africa in the winter of 1975/1976 (Anisoptera: Aeshnidae, Libellulidae. Odonatologica 6(1): 13 - 17

Dumont and Desmet (1990) Transsahara and transmediterraneanmigratory activity of Hemianax ephippiger(Burmeister) in 1988 and 1989 (Anisoptera: Aeshnidae). Odonalologica 19(2): 181-185

Encyclopaedica Britannica (2019) The West African Monsoon. https://www.britannica.com/science/West-African-monsoon

Migrant Dragonflies on facebook : https://www.facebook.com/groups/197169117453555/