Six wings and giants -the earliest fliers and largest insects that ever lived

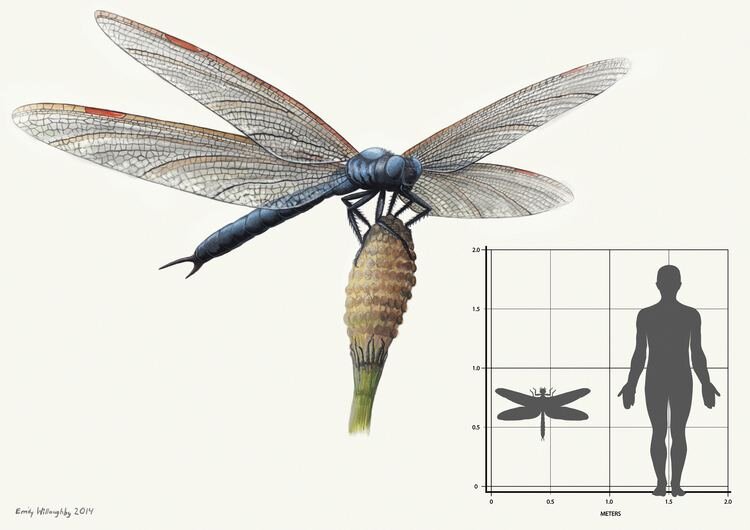

Meganeura spp by Emily Willoughby

Giants

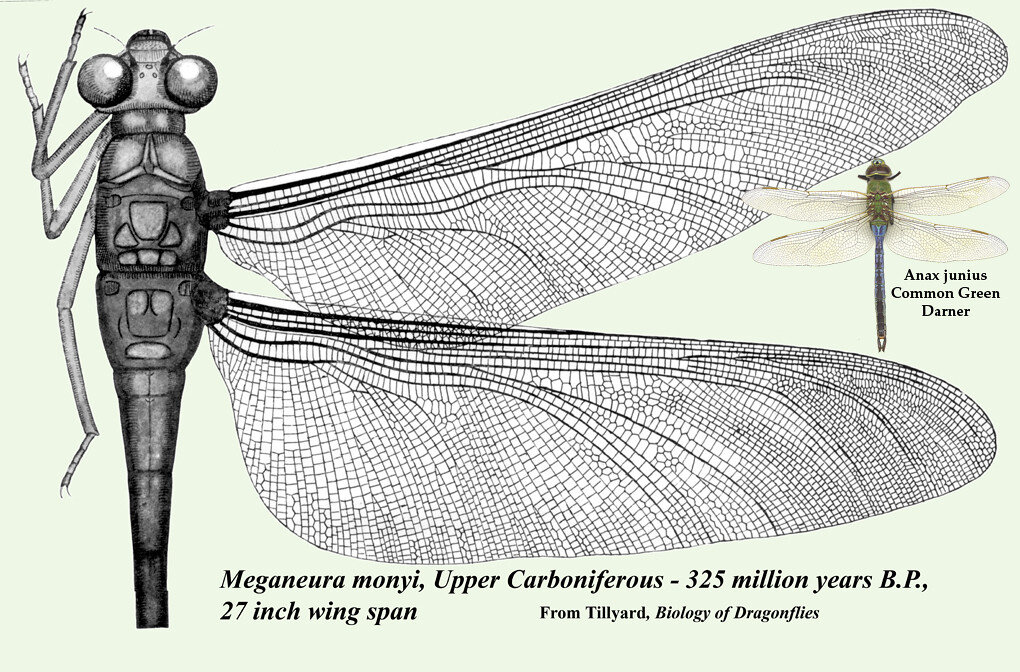

The Meganisopterans, or griffenflies, lived 250-300 million years ago (mya). The planet they inhabited looked very different from now, the continents had not drifted apart and the atmosphere contained more oxygen. During this time, the Carboniferous period (358.9–298.9 mya) and the Permian (298.9–251.9 mya), insects were exceptionally large.

The largest of the known griffenflies are Meganeuropsis permiana, Meganeura monyi and Meganeurites gracilipes

Meganeuropsis permiana by Carim Nahaboo, in actual size next to the artist, twitter: @CNahaboo

Meganeurites gracilipes by Martina Pecharová

Meganeura monyi and Meganeurites gracilipes had wingspans of 70 cm, dwarfing the largest dragonflies of today. Meganeuropsis permiana was even larger, presumed to reach a wingspan of 71 cm. According to recent detailed studies of Meganeurites gracilipes’ mandibles (jaws) and eyes, researchers are convinced that that it, and probably all griffenflies, were aerial predators, thereby very much resembling the now living hawkers and darners.

Why did they grow so big?

There is some debate on why insects of the Carboniferous period acquired gigantism. Insects then and now breathe through body openings that lead to an internal respiratory system, the tracheae, resembling a network of tubes. Oxygen is diffused through the insect’s body via the tracheae, and this process sets an upper limit to body size, an upper limit that was breached by species like Meganeura. In a prehistoric atmosphere containing about 20% more oxygen, as the Carboniferous period, the upper limit for insect body size would have been higher than today, enabling giant insects. However, a hypothesis solely relying on higher oxygen levels for gigantism does not hold, as dragonflies, for example Meganeuropsis permiana, living during the less oxygen rich Permian (298.9–251.9 mya), grew extremely large as well.

Meganeura spp fossil by Ghedoghedo.

Importantly, griffenflies were probably not very heavy insects, as their thin wings made up the main part of their body size. Several extant beetles, like the goliath beetle, can reach as much as 115 grams in weight, and is presumed to be much heavier than the griffenflies. Thus, higher oxygen levels may prove to be a very much less important part of the puzzle than previously thought.

Another explanation to the large size of the insects living during the Carboniferous, and also Permian period, is the lack of aerial vertebrate predators. According to this hypothesis, an arms-race in body size ensued as plant-eating Palaeodictyopterans and their predators, the griffenflies, competed to survive. With nothing larger and deadlier claiming the prehistoric skies, there was a reduced ecological hinder against soft-bodied insects growing large. Of course, the ecosystems inhabited by large insects change with the rise of the dinosaurs and mammals, and today, the largest species of odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), is Megaloprepus caerulatus, a damselfly with a wingspan of a mere 19 cm.

Megaloprepus caerulatus by Alexey Yakovlev

Six wings

Insects were the first animals to take to the skies. The ability to power own flight has evolved at least four times in the evolutionary history of animals, but insects were first. It was probably an ancient group related to mayflies and dragonflies that first developed this ability, perhaps has long ago as during Devonian time (419.2–358.9 mya). One of the earliest fossils found where wings are actually visible is the stunning Delitzschala bitterfeldensis, a so called Palaeodictyopteran that lived 320-323 mya.

Delitzschala bitterfeldensis

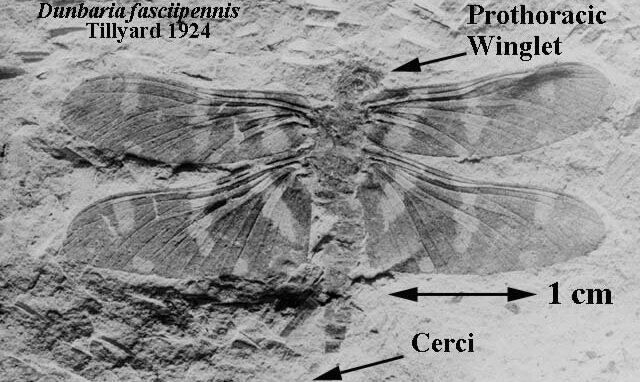

Dunbaria fasciipennis

Delitzschala looks very similar to a dragonfly, but unlike the dragonflies, it is not a predator, but a plant eater, a herbivore. We do not know the colour that these magnificent fliers had, but the patterns on their wings are still visible in the fossils. Looking closer, it is also notable, that this Palaeodictyopteran has a third pair of wings. These so called “winglets” situated on either side of the head is not present on any extant dragonfly, and is a feature that died out when these Palaeodictyopterans disappeared about 252 mya. Another dragonfly-like insects with six wings, that is placed among the Palaeodictyopterans, is a species called Dunbaria fasciipennis.

Delitzschala bitterfeldensis from Brauckmann & Schneider 1996

Dunbaria fasciipennis

Where did they go?

It has been theorised that a change in plant life during Permian time lead to the extinction of the Palaeodictyopterans. The Palaeodictyoptera mouthparts suggest that they fed on liquid food of plant origin, and during the end of the Permian the vegetation changed drastically, with a severe decline in coniferous plants.

The end of the Permian is marked by a devastating mass-extinction event, to date the largest known in history. About 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species disappeared. It also became the largest known mass extinction of insects. The griffenflies disappeared during this time, along with the six-winged Palaeodictyopterans, suggesting that they also failed to adapt to the great changes that took place across most ecosystems at the time.

Studies of the wings of griffenflies have revealed that their wings were less refined than today’s dragonflies’. This reduced aerial manoeuvrability, and the appearance of predators such as flying dinosaurs, birds and bats, eventually led to the demise of the griffenflies.

An unidentified species of Palaeodictyoptera by Jarmila Kukalova-Peck, Delitzschala bitterfeldensis by Elke Gröning

References

Bechly, G (2004). "Evolution and systematics". In Hutchins, M.; Evans, A.V.; Garrison, R.W. & Schlager, N. (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Insects (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. pp. 7–16.

Brauckmann & Schneider (1996). ”Ein unter-karbonisches Insekt aus dem Raum Bitterfeld/Delitz (Pterygota, Arnsbergium, Deutschland)”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte: 17-30.

Engel et al (2013), In: Arthropod Biology and Evolution: “Insect Wings: The Evolutionary Development of Nature’s First Flyers”, pp 269-298.

Kukalova-Peck (1970) Revisional study of the order Palaeodictyoptera in the Upper Carboniferous shales of Commentary, France. Part III. Psyche A Journal of Entomology, vol 77, sid 1-44 - DOI: 10.1155/1969/74019

Nel et al (2018). “Palaeozoic giant dragonfies were hawker predators”, Scientific Reports 8:12141, DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-30629-w